The Streams API is one of the most powerful features introduced in Java 8. It brings functional-style data processing to Java, allowing you to write cleaner, more expressive, and more maintainable code. With Streams, you can filter, transform, and process data using a fluent, declarative style that removes the need for loops, temporary variables, and manual state management.

Whether you’re preparing for interviews or upgrading your backend skills, understanding Streams is essential for modern Java development.

1. Introduction

The Java Streams API enables you to perform complex data processing in a functional, pipeline-oriented way. Instead of writing loops, mutating variables, or managing indices manually, Streams allow you to process collections elegantly and safely.

✔ Why Streams matter

- Cleaner, more expressive code

- Reduced boilerplate

- Encourages functional programming

- Supports lazy evaluation for performance

- Enables powerful transformations and aggregations

- Helps avoid bugs related to mutable state

Streams work beautifully with lambda expressions and method references, making them a natural extension of Java 8’s functional features.

2. What Exactly Is a Stream?

A Stream is a sequence of elements that supports functional-style operations. A Java Stream is a lazily evaluated, immutable sequence of elements supporting functional-style operations.

It is important to understand what a Stream is not:

✔ A Stream is not a data structure

It does not store elements internally.

✔ A Stream is not reusable

After a terminal operation runs, the stream is consumed forever.

✔ A Stream is not a replacement for a collection

It is a tool to process data from a collection.

✔ A Stream is a pipeline

It describes a series of operations to perform on a data source.

🔹 Example: Traditional Loop vs Stream Pipeline

Without Streams:

List<String> result = new ArrayList<>();

for (String name : names) {

if (name.startsWith("A")) {

result.add(name.toUpperCase());

}

}

With Streams:

List<String> result =

names.stream()

.filter(n -> n.startsWith("A"))

.map(String::toUpperCase)

.toList();

The Stream-based code is shorter, cleaner, and easier to read.

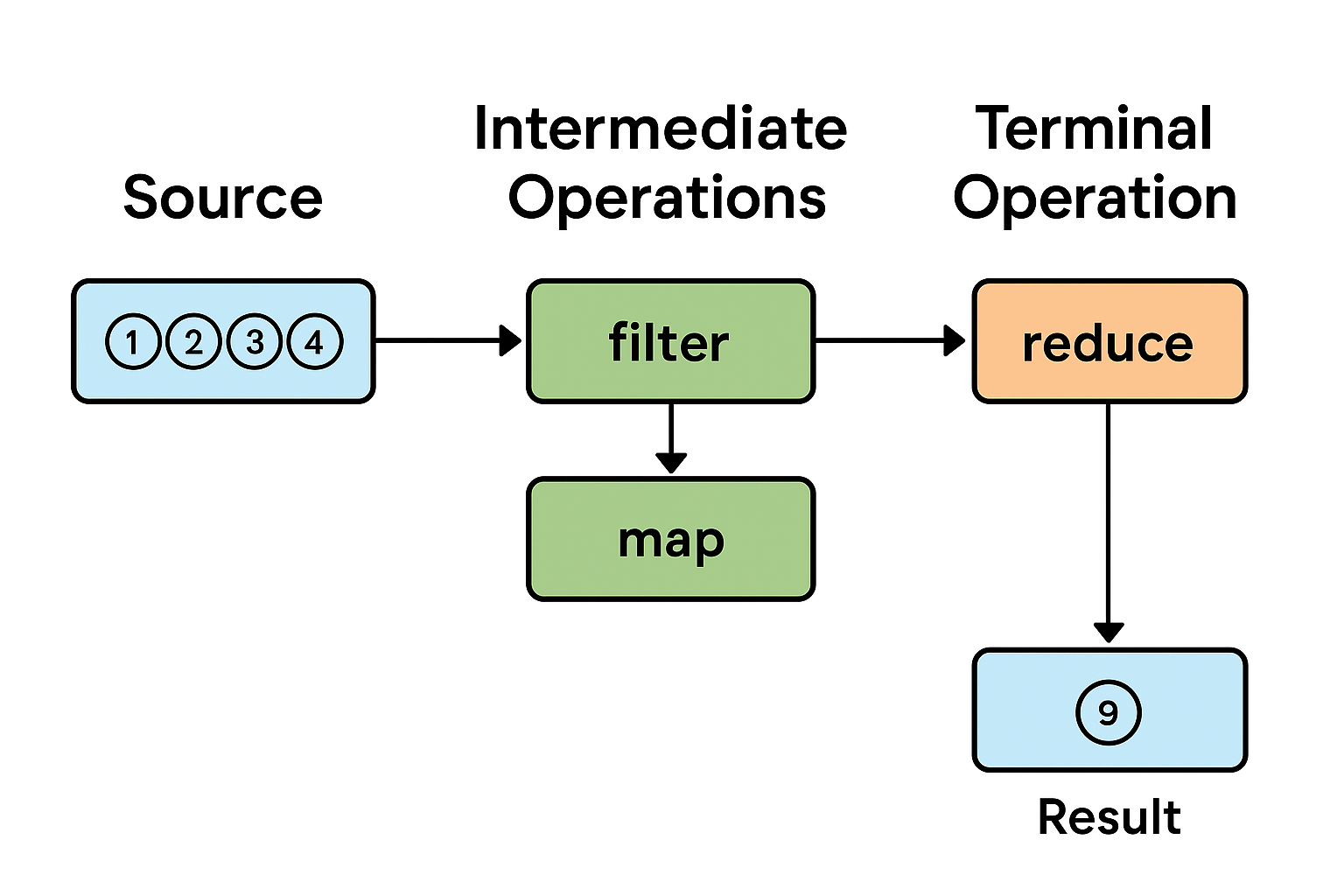

3. Stream Pipeline Architecture

A Stream pipeline always has three stages:

3.1 Source (Starting Point)

The source provides the data for processing.

Common Stream sources:

collection.stream()

Stream.of(1, 2, 3)

Arrays.stream(array)

Files.lines(path)

Anything that implements java.util.stream.BaseStream can act as a source.

3.2 Intermediate Operations (Lazy)

Intermediate operations build the pipeline but do not execute immediately.

These operations return a new Stream and are lazy, meaning nothing happens until later.

Common intermediate operations:

| Operation | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

filter() | Stateless | Keeps elements matching a condition |

map() | Stateless | Transforms each element |

flatMap() | Stateless | Converts nested structures into flat streams |

sorted() | Stateful | Sorts based on comparator |

distinct() | Stateful | Removes duplicates |

limit() | Stateful (Short-circuit) | Stops after a number of elements |

Example:

stream.filter(n -> n > 10)

.map(n -> n * 2);

Still no processing happens yet — Streams are lazy.

3.3 Terminal Operations (Execution Phase)

Only a terminal operation triggers execution of the pipeline.

Common terminal operations:

forEach(...)

collect(...)

reduce(...)

count()

findFirst()

findAny()

anyMatch(...)

allMatch(...)

noneMatch(...)

Example:

List<Integer> result =

numbers.stream()

.filter(n -> n % 2 == 0)

.map(n -> n * 10)

.toList(); // Terminal — execution happens here

4. Lazy Evaluation in Streams

Lazy evaluation is one of the most powerful and misunderstood aspects of the Java Streams API. It affects performance, execution order, and how your code behaves internally.

A Stream pipeline is not executed immediately. Instead:

- Intermediate operations build a recipe

- Terminal operations trigger execution

- Elements are processed one-by-one, not stage-by-stage

- The pipeline evaluates just enough to produce results

This leads to massive performance benefits in filtering, mapping, short-circuiting, and large data processing.

4.1 What Does Lazy Evaluation Actually Mean?

When you write:

numbers.stream()

.filter(n -> n > 10)

.map(n -> n * 2)

Nothing happens yet.

Java simply records:

- A filter operation

- A map operation

The work happens only when you call a terminal operation:

.toList(); // or forEach(), collect(), reduce(), etc.

4.2 How Streams Process Elements (Per-Element Model)

Developers often think Streams process like this:

WRONG mental model (batch mode):

- Run filter on all elements

- Then run map on all filtered elements

- Then run terminal op on all mapped elements

But Streams actually work like this:

CORRECT mental model (per-element):

take element 1 → filter → map → terminal

take element 2 → filter → map → terminal

take element 3 → filter → map → terminal

...

This is why Streams can short-circuit effectively.

4.3 Lazy Evaluation Example

Code:

List<Integer> numbers = List.of(1, 2, 3, 4);

numbers.stream()

.filter(n -> {

System.out.println("Filtering " + n);

return n % 2 == 0;

})

.map(n -> {

System.out.println("Mapping " + n);

return n * 10;

})

.forEach(System.out::println);

Output:

Filtering 1

Filtering 2

Mapping 2

20

Filtering 3

Filtering 4

Mapping 4

40

What this shows:

- Filtering happens one element at a time

- As soon as filter passes, map executes immediately

- No intermediate collections are created

- Streams optimize by not doing unnecessary work

4.4 Benefits of Lazy Evaluation

✔ More Efficient

Processes only what is needed.

✔ Enables Short-Circuiting

Operations like:

findFirst()anyMatch()limit()

Stop processing early.

✔ Supports Infinite Streams

Streams like:

Stream.generate(Math::random)

work only because evaluation is lazy.

✔ Improved Memory Use

No intermediate lists or arrays.

5. Short-Circuiting Operations

Short-circuiting is when a stream terminal or intermediate operation stops early once a condition is met.

This is a core performance feature in Streams.

5.1 Short-Circuiting Intermediate Operations

✔ limit(n)

Stops after processing n elements.

numbers.stream()

.filter(n -> n > 10)

.limit(2)

.toList();

Even if the list has 10,000 elements, processing stops after 2 matches.

5.2 Short-Circuiting Terminal Operations

✔ anyMatch()

names.stream()

.anyMatch(n -> n.startsWith("A"));

Stops at the first match.

✔ findFirst() / findAny()

Stream.of("A", "B", "C")

.findFirst()

.get();

Processes only the first element.

Why This Matters

Short-circuiting combined with lazy evaluation allows Streams to:

- Run faster

- Use less CPU

- Use less memory

- Avoid unnecessary iterations

This is one of the biggest advantages over imperative loops.

6. Stateful vs Stateless Operations

Streams have two types of intermediate operations.

6.1 Stateless Operations

These do not depend on other elements:

map()filter()flatMap()

They process each element independently.

Benefits:

- Fast

- Parallelizable

- Predictable

6.2 Stateful Operations

These must examine or buffer multiple elements:

sorted()distinct()limit()(partially stateful)skip()

Example:

numbers.stream().sorted().toList();

Sorting requires examining all elements before producing output.

Downsides:

- Slower

- Higher memory usage

- Not ideal for huge unbounded streams

- Sometimes inefficient in parallel streams

7. Common Stream Patterns

Streams shine when expressing common data-processing tasks in a fluent, readable pipeline. Here are the most widely used patterns every Java developer should know.

7.1 Filtering Elements

Use filter() to keep only elements that match a condition.

List<String> result =

names.stream()

.filter(n -> n.startsWith("A"))

.toList();

7.2 Transforming Values with map()

map() transforms one value into another.

List<Integer> lengths =

names.stream()

.map(String::length)

.toList();

7.3 Flattening Nested Structures with flatMap()

When each element contains a collection, use flatMap() to flatten them.

List<String> allWords =

books.stream()

.flatMap(book -> book.getWords().stream())

.toList();

7.4 Collecting Results

Use collect() or .toList(), .toSet() in Java 16+.

List<String> sorted =

names.stream()

.sorted()

.toList();

7.5 Reducing Values

reduce() combines elements to produce a single result.

int sum =

numbers.stream()

.reduce(0, Integer::sum);

7.6 Grouping and Partitioning (Powerful Collectors)

Grouping:

Map<Integer, List<String>> byLength =

names.stream()

.collect(Collectors.groupingBy(String::length));

Partitioning:

Map<Boolean, List<Integer>> evenOdd =

numbers.stream()

.collect(Collectors.partitioningBy(n -> n % 2 == 0));

8. Parallel Streams

Parallel Streams allow operations to be performed concurrently using the common ForkJoinPool.

8.1 What Are Parallel Streams?

Just add .parallel():

numbers.parallelStream()

.map(n -> n * 2)

.toList();

Java splits the stream into chunks and processes them on multiple threads.

8.2 When Parallel Streams Are Useful

Use them for:

- CPU-intensive operations

- Large data sets

- Pure functions (no shared state)

- Order-insensitive processing

Example:

long count =

LongStream.range(1, 1_000_000)

.parallel()

.filter(n -> n % 2 == 0)

.count();

8.3 When NOT to Use Parallel Streams

Avoid them if:

- Your operations mutate shared state

- You’re working with I/O operations

- Order matters

- Data sets are small

- You’re running inside application servers with managed thread pools

- They hurt readability more than they help

Parallelism is powerful but not free — use it wisely.

9. Common Mistakes Developers Make with Streams

Streams make code elegant — but they also introduce pitfalls. Avoid these common mistakes:

9.1 Modifying External State in a Stream

Bad:

List<Integer> result = new ArrayList<>();

numbers.stream()

.map(n -> n * 2)

.forEach(result::add); // mutating external state!

This breaks functional purity and can cause issues in parallel streams.

Correct:

List<Integer> result =

numbers.stream()

.map(n -> n * 2)

.toList();

9.2 Forgetting the Terminal Operation

Streams don’t run unless you trigger a terminal op.

numbers.stream().filter(n -> n > 10); // does nothing

9.3 Using Streams When a Simple Loop Is Cleaner

Streams are great, but not for everything.

Bad:

IntStream.range(0, list.size()).forEach(i -> ... );

Good:

for (int i = 0; i < list.size(); i++) { ... }

9.4 Using Parallel Streams Incorrectly

Common mistakes:

- Doing I/O in parallel streams

- Relying on shared mutable state

- Expecting parallelization to always be faster

- Using parallel streams inside web servers (bad idea)

9.5 Creating Too Many Intermediate Streams

Bad:

list.stream().map(...).stream().filter(...); // redundant

9.6 Overusing Streams

If your code becomes harder to read, prefer loops.

10. Best Practices for Using Streams

✔ Keep pipelines readable

Break long pipelines into multiple lines.

✔ Prefer method references

names.stream().map(String::toUpperCase)

Cleaner than:

names.stream().map(n -> n.toUpperCase())

✔ Avoid shared mutable state

Pure functions are safe; mutation is dangerous.

✔ Use Collectors effectively

Collectors simplify grouping, mapping, joining, and reducing.

Example:

Map<Integer, Long> countByLength =

names.stream()

.collect(Collectors.groupingBy(String::length, Collectors.counting()));

✔ Use sequential streams unless parallel provides measurable improvement

Parallel should always be a conscious choice.

11. Summary

Streams offer a powerful way to process collections using functional patterns.

Key ideas to remember:

- Streams work in pipelines: source → intermediate → terminal

- Intermediate operations are lazy

- Terminal operations trigger execution

- Streams process one element at a time

- Short-circuit operations improve performance

- Stateful operations require extra memory

- Parallel streams can help — but only in the right situations

- Follow best practices to avoid pitfalls

- Parallel streams are not always the right choice for concurrency; for fine-grained control over thread management, task scheduling, and resource usage, see ExecutorService and thread pools in Java — when parallel streams are not enough .

Mastering Streams gives you cleaner code, fewer bugs, and stronger interview performance.

TL;DR

The Java Streams API enables functional, lazy, pipeline-based processing of collections using source, intermediate, and terminal operations. Streams improve readability, performance, and correctness when used properly.

View Full Source Code on GitHub

Master Lambda Expressions, Functional Interfaces & Optional in Java 8

What is the Java Streams API in simple terms?

The Java Streams API provides a functional, pipeline-based way to process collections of data.

Instead of writing loops, you define what should happen to the data using operations like filter, map, and collect. Streams focus on declarative data processing, not data storage.

What is a stream pipeline?

A stream pipeline consists of three parts:

Source – where data comes from (collection, array, I/O)

Intermediate operations – transformations like filter, map, sorted

Terminal operation – triggers execution (forEach, collect, reduce)

Until a terminal operation is called, nothing executes.

Why are Java streams lazily evaluated?

Streams are lazy to improve performance and efficiency.

Lazy evaluation means:

Operations execute only when needed

Processing stops as soon as the result is determined

Intermediate results are not stored

This allows optimizations like short-circuiting and element-by-element processing.

Can Java streams modify the original collection?

No.

Streams are immutable views of data.

The source collection is never modified

Each operation produces a new stream

Side effects are discouraged

This design makes streams safer and easier to reason about.

Why can a stream be consumed only once?

Streams represent a single-use computation pipeline.

Once a terminal operation executes:

The stream is closed

The internal state is consumed

Reusing it would be unsafe

If you need to process data again, create a new stream from the source.

What is the difference between map() and flatMap()?

map() transforms each element into exactly one elementflatMap() transforms each element into zero or more elements and flattens the result

Example use case for flatMap():

Processing nested collections

Splitting strings into words

Merging multiple streams into one

When should parallel streams be avoided?

Parallel streams should be avoided when:

Tasks involve blocking I/O

Execution order matters

Workload is small

You need custom thread management

You run inside application servers or shared environments

For controlled concurrency, prefer ExecutorService and thread pools.

Are parallel streams faster than sequential streams?

Not always.

Parallel streams may be slower when:

Overhead of thread coordination outweighs work

Data size is small

CPU cores are limited

Tasks are not CPU-bound

Always benchmark before assuming performance gains.

Are Java streams suitable for production systems?

Yes — when used correctly.

Best practices:

Keep stream operations side-effect free

Avoid heavy logic inside lambdas

Use sequential streams by default

Profile before using parallel streams

Misuse often causes more problems than streams themselves.

Are Java streams the same as reactive streams?

No.

Java Streams are synchronous and pull-based

Reactive streams are asynchronous and push-based

Streams are for in-memory data processing, not event streams or async pipelines.

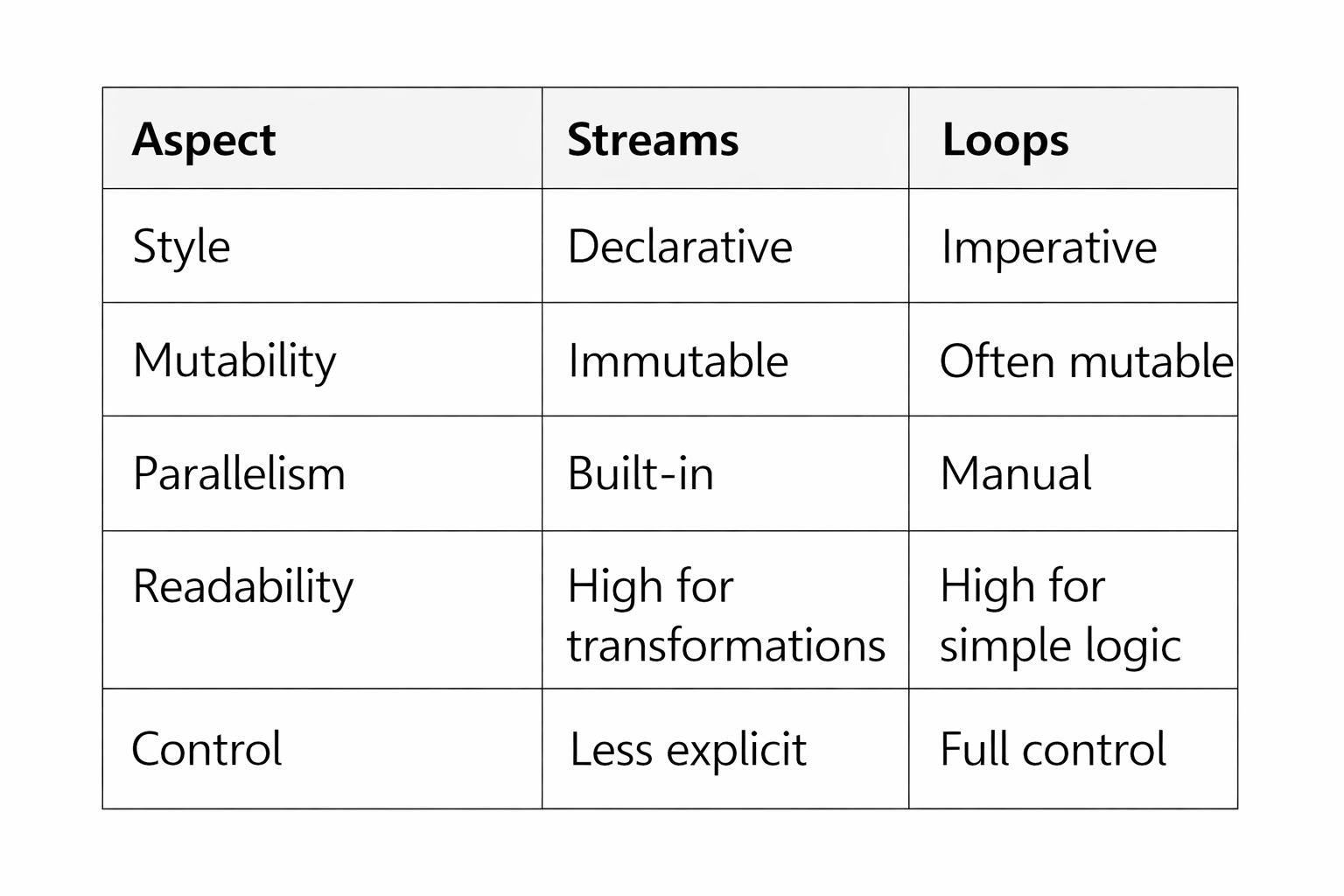

What is the difference between streams and loops?

Streams excel at data transformation, loops excel at complex control flow.

12. References & Further Reading

- Oracle Java Streams Tutorial

https://docs.oracle.com/javase/8/docs/api/java/util/stream/package-summary.html - Java Language Specification (Streams)

https://docs.oracle.com/javase/specs/ - Effective Java (3rd Edition) — Joshua Bloch

Item 48: “Use Streams Judiciously” - Official Collectors Documentation

https://docs.oracle.com/javase/8/docs/api/java/util/stream/Collectors.html

Did this tutorial help you?

If you found this useful, consider bookmarking Code & Candles or sharing it with a friend.

Explore more tutorials