A comprehensive exploration of thread pools, task execution, concurrency internals, and performance engineering in the JVM.

Understanding concurrency is one of the most significant upgrades in a Java developer’s career.

ExecutorService is where real-world Java concurrency begins.

Modern Java applications—backend services, distributed systems, real-time data processors—depend heavily on controlled, predictable, and efficient concurrency. Poor concurrency decisions rarely fail immediately; instead, they surface later as latency spikes, thread starvation, memory pressure, or production outages under load.

ExecutorService and thread pools provide a disciplined way to execute asynchronous work without manually managing threads. This guide goes beyond basic usage and explains how ExecutorService works internally, why certain configurations fail, and how to design thread pool strategies that scale safely in production systems.

This executorservice thread pools java guide explains how to design, size, and operate production-grade thread pools safely in real-world Java applications.

How to Think About Concurrency in Java

ExecutorService and thread pools in Java provide a structured, scalable way to execute asynchronous tasks while maintaining control over concurrency, performance, and system stability.

Concurrency in Java is not about creating more threads.

It is about controlling how work is scheduled, executed, and completed under constrained resources.

Threads are expensive. Each thread consumes memory, competes for CPU time, and introduces coordination overhead. Unbounded thread creation often reduces performance instead of improving it due to excessive context switching and contention.

ExecutorService solves this by decoupling task submission from task execution. Applications submit tasks as units of work, and the executor decides when, where, and how many tasks run concurrently using a bounded set of worker threads.

A well-designed concurrency model focuses on:

- Limiting parallelism instead of maximizing it

- Matching thread pool size to workload characteristics

- Preventing unbounded queues and blocking operations

- Ensuring predictable behavior under load

Thinking in terms of controlled execution, not raw thread creation, is the key to building scalable Java systems.

Why Thread Pools Exist (and Why new Thread() Is Not Enough)

ExecutorService and Thread Pools in Java — Core Concepts

Creating threads manually often looks simple:

new Thread(task).start();But modern Java applications need far more than simplicity.

They require control, predictability, and performance under load.

Below are the fundamental problems with raw thread creation—and why thread pools exist.

1. Threads Are Expensive to Create

Each thread consumes significant system resources:

- Stack memory (typically ~1 MB per thread)

- Operating system scheduler overhead

- JVM-managed thread metadata

Accidentally creating hundreds or thousands of threads—something that does happen in production—can exhaust memory or overwhelm the OS scheduler.

2. Threads Have an Unbounded Lifecycle

If you create 200 threads manually, you now need to:

- Track them

- Interrupt them

- Join them

- Handle uncaught exceptions

- Restart them if they fail

This quickly becomes unmanageable and error-prone.

Thread pools centralize lifecycle management instead of scattering it across the application.

3. No Thread Reuse → Huge Performance Cost

Thread creation is slow.

Starting threads repeatedly for short-lived tasks wastes CPU time and increases latency.

Thread pools solve this by reusing worker threads, much like database connection pools reuse connections.

4. No Task Queueing Model

With raw threads, you cannot express concepts like:

- Accept up to 20 tasks but execute only 4 concurrently

- Queue tasks until capacity frees up

- Schedule tasks to run every 5 seconds

Thread pools introduce explicit task queues, enabling backpressure and load control.

5. No Clean Way to Get Return Values

If a thread computes a result, you’re forced into awkward patterns:

- Shared mutable variables

- Latches

- Callbacks

- Blocking queues

ExecutorService introduces Callable, Future, and composable async workflows that are safer and easier to reason about.

6. No Structured Shutdown Strategy

Raw threads can easily:

- Leak

- Hang

- Become orphaned

- Block JVM shutdown

Thread pools provide centralized shutdown semantics:

shutdown()shutdownNow()- graceful vs forceful termination

This is critical for real-world services.

Conclusion

Modern concurrency requires a predictable, tunable, centralized mechanism for executing tasks. That mechanism is ExecutorService.

Java Thread Execution Lifecycle

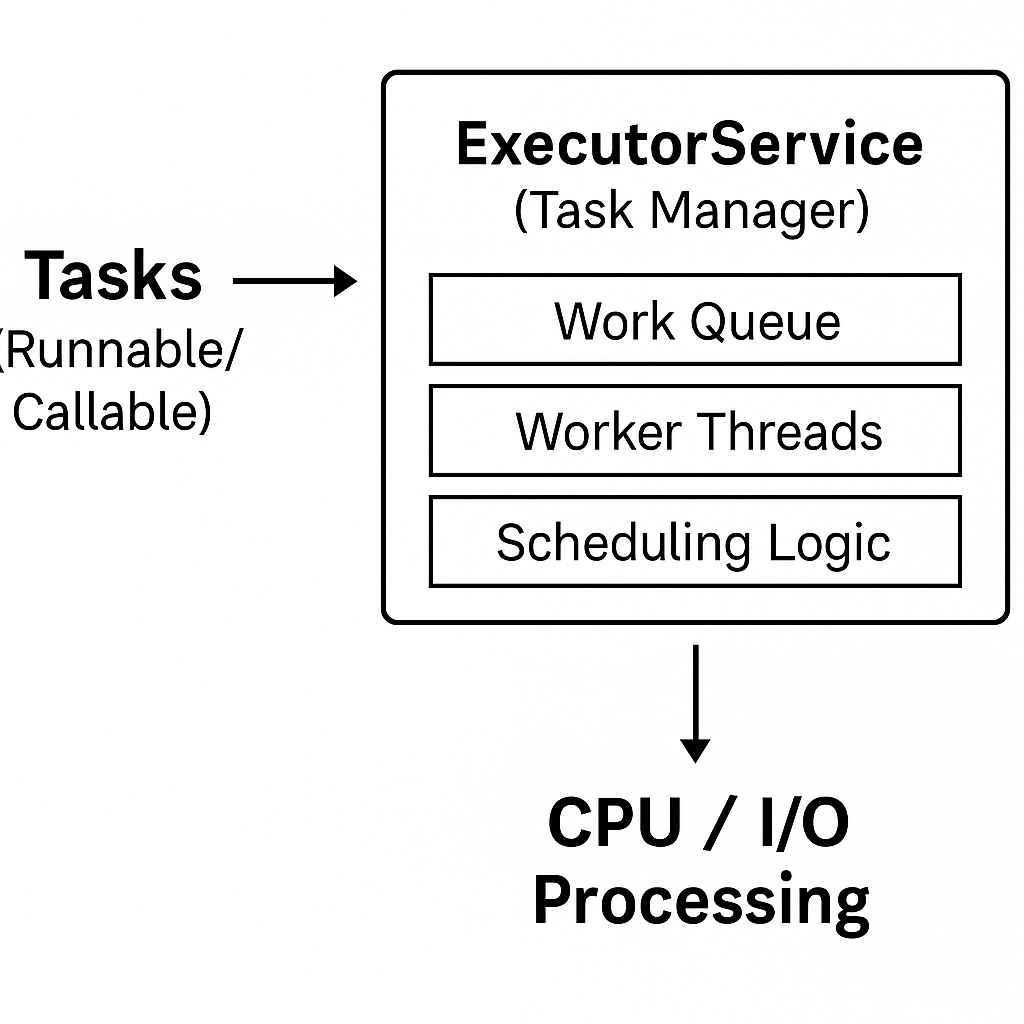

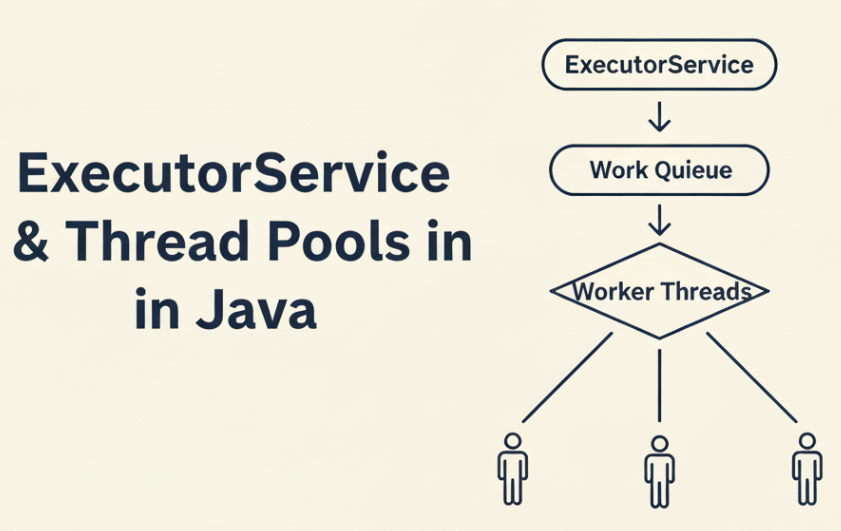

At a high level, every ExecutorService follows the same execution flow:

Task Submission → Queue → Worker Thread → Execution → Completion- Task Submission

ARunnableorCallableis submitted to the executor. - Task Queueing

If no worker thread is immediately available, the task is placed into a queue. - Worker Thread Execution

A worker thread takes a task from the queue and executes it. - Completion & Reuse

After execution, the thread is reused for the next task instead of being destroyed.

This lifecycle allows Java to reuse threads efficiently and avoid the overhead of repeated thread creation.

Java concurrency revolves around a structured execution flow that controls how tasks move from submission to execution. At a high level, tasks are submitted to an executor, queued, and executed by worker threads.

ExecutorService Internals — How It Really Works

Under the hood, nearly all ExecutorService implementations in Java are backed by ThreadPoolExecutor.

At a high level, ThreadPoolExecutor has three core pieces:

- Work Queue — where tasks wait before execution

- Worker Threads — threads that repeatedly pull and run tasks

- Pool Size Controls — rules that govern when threads are created, reused, or rejected

1. The Work Queue

The work queue stores submitted tasks until a worker thread picks them up.

Common queue types and what they imply:

LinkedBlockingQueue

- Unbounded by default (theoretical max:

Integer.MAX_VALUE) - Commonly used by

Executors.newFixedThreadPool(...) - ✅ Stable thread count

- ⚠️ Risk: queue can grow without limit → memory pressure, latency spikes, long tail times under load

SynchronousQueue

- No storage — a task must be handed directly to a thread immediately

- Used by

Executors.newCachedThreadPool(...) - ✅ Great for short bursty tasks

- ⚠️ Risk: pool can explode into many threads until max limits are hit (or system becomes unstable)

DelayedWorkQueue

- Used by

ScheduledThreadPoolExecutorfor delayed / periodic tasks - Enables scheduling semantics (delay, fixed-rate, fixed-delay)

Key idea: Your queue choice changes failure mode:

- Unbounded queue → memory/latency failure

- No queue (handoff) → thread explosion failure

2. Worker Threads

Worker threads are created and managed by ThreadPoolExecutor.

Each worker thread typically:

- takes tasks from the queue

- runs the task

- loops and tries to take the next task

- stays alive until idle timeout or shutdown

This is why thread pools scale better than creating new threads: threads are reused instead of created/destroyed repeatedly.

3. Pool Size Controls

ThreadPoolExecutor uses pool size rules to decide:

- when to create threads

- when to queue tasks

- when to reject tasks

Two key limits matter the most:

Core Pool Size (corePoolSize)

- Minimum number of worker threads kept alive (even if idle)

- Defines the “always available” concurrency baseline

Maximum Pool Size (maximumPoolSize)

- Hard cap on total threads

- Prevents unbounded thread growth

In practice:

- If workers <

corePoolSize→ create new threads - Else → queue tasks (depending on queue)

- If queue is full and workers <

maximumPoolSize→ create more threads - If queue is full and workers ==

maximumPoolSize→ reject tasks

4. Rejection Policies

When the executor is saturated, RejectedExecutionHandler decides what happens.

Common policies:

DiscardOldestPolicy → drops the oldest queued task (rarely safe)

AbortPolicy (default) → throws RejectedExecutionException

CallerRunsPolicy → caller thread runs task (backpressure, but can slow request threads)

DiscardPolicy → drops the task silently (dangerous)

Types of Thread Pools and When to Use Them

Java provides several built-in thread pool implementations through the Executors factory class.

While these abstractions are convenient, choosing the wrong thread pool type is one of the most common causes of concurrency bugs and performance issues in production systems.

This section explains how each thread pool behaves, what problem it is designed to solve, and when it becomes dangerous.

Fixed Thread Pool (newFixedThreadPool)

A fixed thread pool maintains a constant number of worker threads.

ExecutorService executor = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(8);How it works

- Uses a fixed number of threads

- Tasks beyond that limit are placed into a queue

- Threads are reused for the lifetime of the executor

When it works well

- CPU-bound workloads

- Predictable concurrency limits

- Systems where stability is more important than burst throughput

Hidden risk

- Uses an unbounded

LinkedBlockingQueue - Under load, tasks accumulate indefinitely

- Latency grows silently while memory usage increases

Real-world guidance

Use fixed thread pools only when task arrival rate is controlled or when you explicitly replace the queue with a bounded one via ThreadPoolExecutor.

Cached Thread Pool (newCachedThreadPool)

A cached thread pool creates new threads on demand and reuses idle ones.

ExecutorService executor = Executors.newCachedThreadPool();How it works

- No internal queue

- Tasks are handed directly to threads

- New threads are created if none are available

- Idle threads are terminated after a timeout

When it works well

- Short-lived, non-blocking tasks

- Low and unpredictable traffic

- Burst workloads with fast completion times

Hidden risk

- No upper bound on thread creation

- Under blocking I/O or slow downstream systems, thread count can explode

- Can overwhelm CPU, memory, or external services

Real-world guidance

Cached thread pools are unsafe for server-side request handling.

Avoid them in web applications unless you fully understand the workload.

Single Thread Executor (newSingleThreadExecutor)

A single-thread executor processes tasks sequentially.

ExecutorService executor = Executors.newSingleThreadExecutor();How it works

- Exactly one worker thread

- Tasks execute strictly in submission order

- Uses an unbounded queue

When it works well

- Serializing access to shared resources

- Background maintenance jobs

- Event processing where ordering matters

Hidden risk

- Single point of throughput limitation

- Unbounded queue can still grow under load

Real-world guidance

Best used for coordination tasks, not throughput-heavy workloads.

Scheduled Thread Pool (newScheduledThreadPool)

Designed for delayed and periodic execution.

ScheduledExecutorService scheduler = Executors.newScheduledThreadPool(2);How it works

- Uses a time-based priority queue

- Supports delayed and periodic tasks

- Threads execute tasks when their delay expires

When it works well

- Periodic maintenance jobs

- Polling tasks

- Time-based workflows

Hidden risk

- Long-running tasks delay subsequent executions

- Exceptions can silently stop scheduled tasks

Real-world guidance

- Always keep scheduled tasks short and defensive.

- Avoid blocking operations inside scheduled jobs.

Custom ThreadPoolExecutor (Recommended for Production)

For real systems, ThreadPoolExecutor provides full control.

ExecutorService executor = new ThreadPoolExecutor(

8, // corePoolSize

16, // maximumPoolSize

60, TimeUnit.SECONDS, // idle timeout

new ArrayBlockingQueue<>(100),

new ThreadPoolExecutor.CallerRunsPolicy()

);Why this is the preferred approach

- Bounded concurrency

- Explicit backpressure

- Controlled failure behavior

- Predictable latency characteristics

When you should use it

- Web servers

- Microservices

- Messaging consumers

- Any system under unpredictable load

Real-world guidance

Never rely on default executors in production systems.

Always design your thread pool based on:

- Task type (CPU vs I/O)

- Failure tolerance

- Queueing behavior

- Backpressure strategy

Choosing the Right Thread Pool Size — A Real-World Strategy

Choosing the right thread pool size is one of the most important design decisions when using ExecutorService.

Too few threads underutilize the CPU. Too many threads cause excessive context switching, latency spikes, and sometimes complete system unresponsiveness.

This section provides a practical, production-oriented approach to sizing thread pools based on how tasks actually behave.

CPU-Bound Tasks (Pure Computation)

CPU-bound tasks spend most of their time performing calculations:

- encryption

- image processing

- in-memory aggregation

- simulations

If you create as many threads as CPU cores and keep them all busy, you leave no room for:

- the OS scheduler

- JVM GC and JIT threads

- logging, metrics, and async callbacks

- admin or operational tasks on the machine

In real systems, this can make the host feel “frozen.”

Recommendation

Keep CPU-bound pools slightly below the number of cores:

cpuPoolSize ≈ numberOfCores - 1 // or cores - 2 for safer headroomExample

- Machine: 8 logical cores

- CPU-bound analytics workload

cpuPoolSize = 7 threadsThis keeps CPUs busy while leaving breathing room for the OS and JVM.

I/O-Bound Tasks (Waiting on Network / DB / Disk)

I/O-bound tasks spend most of their time waiting:

- database queries

- REST API calls

- file reads/writes

- message broker calls

While a thread is blocked on I/O, it is not using the CPU.

The OS can schedule other threads on that core in the meantime.

In web applications, thread pools are not used in isolation but are tightly integrated with the framework lifecycle. The article Spring Boot and Spring Framework internals explains how Spring manages request threads, filters, and application context initialization.

This is where having more threads than cores improves throughput.

Rule of Thumb (Goetz)

optimalPoolSize = numberOfCores × (1 + waitTime / computeTime)This is why production web servers often run hundreds of worker threads for heavy I/O workloads.

Mixed Workloads (Most Real Systems)

Most backend systems contain both:

- CPU-bound work (parsing, business logic)

- I/O-bound work (DB calls, HTTP requests)

The safest approach is to separate them:

int cores = Runtime.getRuntime().availableProcessors();

ExecutorService cpuPool = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(cores - 1);

ExecutorService ioPool = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(cores * 20); // start point, then tuneRoute tasks explicitly:

- heavy computation →

cpuPool - I/O operations →

ioPool

This prevents slow I/O from clogging CPU threads.

Quick Reference Cheatsheet

| Workload Type | Starting Point |

|---|---|

| Pure CPU-bound | cores - 1 (or cores - 2 in prod) |

| Light I/O-bound | 2 × cores |

| Heavy I/O-bound | cores × 20 to cores × 50 |

| Mixed workloads | Separate CPU and I/O pools |

| Unknown | Start conservative, then measure |

Measure, Don’t Guess

Thread pool sizing should never be hardcoded blindly.

Use metrics and profiling to tune over time.

Track:

- CPU utilization

- queue length and wait time

- active thread count

- task execution time vs wait time

- rejected tasks

Simple signals

- CPU idle + queued tasks → add threads (I/O)

- CPU saturated + rising latency → reduce threads

- OS feels sluggish → CPU pool is too large

Recap

- For CPU-bound work: keep the pool size below the number of cores.

- For I/O-bound work: it’s safe and often necessary to have many more threads than cores, because most time is spent waiting.

- For mixed workloads: split into separate CPU and I/O pools, and size each according to its behavior.

- Always leave headroom for the OS and JVM — a machine does more than just run your threads.

You can now talk about thread pool sizing confidently in code reviews, performance tuning sessions, and interviews — and you have a solid mental model that matches what you’ve already seen in your real projects.

Summary: Choosing the Right Thread Pool

| Thread Pool Type | Best For | Primary Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed Thread Pool | CPU-bound tasks | Unbounded queue |

| Cached Thread Pool | Short bursty tasks | Unbounded threads |

| Single Thread Executor | Ordered execution | Throughput bottleneck |

| Scheduled Thread Pool | Timed tasks | Task delays |

| Custom ThreadPoolExecutor | Production workloads | Requires tuning |

Thread Pool Tradeoffs and Common Pitfalls

Common Thread Pool Pitfalls in Production Systems

Thread pools often work perfectly in development and fail spectacularly in production.

The reason is simple: most failures emerge only under sustained load, partial outages, or degraded downstream systems.

This section highlights the most common—and costly—thread pool mistakes seen in real systems.

1. Treating Thread Pools as Infinite Resources

A frequent misconception is that thread pools “scale automatically.”

They do not.

- Threads consume memory and CPU

- Context switching has real cost

- The OS scheduler is a shared resource

Unbounded growth (threads or queues) merely delays failure and makes it harder to diagnose.

Rule:

Every thread pool must have a hard limit—either on threads, queue size, or both.

2. Blocking I/O in CPU-Bound Thread Pools

One of the most damaging mistakes is mixing blocking I/O into CPU pools.

Example:

- CPU pool sized at

cores - 1 - Task performs a database call

- Threads block waiting on I/O

- CPU cores sit idle

- Requests queue up

- Latency spikes

Result: throughput collapses even though CPU usage looks low.

Fix:

Separate pools for:

- CPU-bound work

- I/O-bound work

Never let slow I/O consume CPU executor threads.

3. Sharing One Executor for Unrelated Workloads

Using a single executor for:

- HTTP request handling

- Background jobs

- Metrics publishing

- Cache refreshes

creates implicit coupling.

If one workload stalls or spikes, everything else suffers.

Fix:

Use purpose-specific executors with clear ownership and sizing.

Isolation is one of the cheapest reliability improvements you can make.

4. Ignoring RejectedExecutionHandler Behavior

Rejection is not a failure—it is a signal.

Default behavior (AbortPolicy) throws exceptions.

Other policies silently drop tasks or push work onto the caller thread.

Each has consequences:

AbortPolicy→ noisy but visible failureCallerRunsPolicy→ backpressure but may block request threadsDiscardPolicy→ silent data lossDiscardOldestPolicy→ unpredictable behavior

Fix:

Choose a rejection strategy deliberately and log rejections aggressively.

5. Forgetting to Shut Down Executors

ExecutorServices are not daemon-based by default.

If you:

- create executors dynamically

- forget to shut them down

you risk:

- thread leaks

- blocked JVM shutdown

- resource exhaustion over time

Fix:

Always shut down executors during application shutdown:

executor.shutdown();

executor.awaitTermination(30, TimeUnit.SECONDS);6. Relying on Defaults in Production

Executors.newFixedThreadPool(...) and friends are convenient—but dangerous.

They hide:

- unbounded queues

- default thread factories

- default rejection policies

Fix:

For production systems, prefer explicit ThreadPoolExecutor configuration so that behavior is visible, tunable, and observable.

7. Tuning Once and Never Revisiting

Thread pool sizing is not “set and forget.”

Changes in:

- traffic patterns

- payload size

- downstream latency

- hardware

- JVM version

can invalidate old assumptions.

Fix:

Revisit executor configuration whenever performance characteristics change.

Key Takeaway

Thread pools are load-control mechanisms, not performance hacks.

When misused, they:

- amplify latency

- hide failures

- make outages harder to diagnose

When designed deliberately, they:

- protect system stability

- make performance predictable under stress

- provide backpressure

Blocking Tasks in ExecutorService

Blocking calls (e.g., database or network I/O) inside limited thread pools reduce throughput and increase tail latency.

Rule:

Never block CPU-bound executors with I/O work.

Unbounded Queues and Memory Risk

Unbounded queues delay failure but amplify it. When memory fills up, the system crashes abruptly.

Prefer bounded queues with backpressure.

Thread Starvation and Deadlocks

Incorrect pool sharing across unrelated workloads can cause starvation where critical tasks never execute.

Use separate executors for distinct workloads.

ExecutorService vs ForkJoinPool vs Virtual Threads

ExecutorService

- General-purpose concurrency

- Explicit control over threads and queues

ForkJoinPool

- Best for divide-and-conquer workloads

- Uses work-stealing for parallelism

Virtual Threads (Java 21+)

- Lightweight threads managed by the JVM

- Excellent for blocking I/O workloads

- Still require structured concurrency discipline

ExecutorService remains foundational even with virtual threads.

Best Practices for Production-Grade Thread Pools

- Size pools based on workload type (CPU vs I/O)

- Avoid blocking operations in shared executors

- Use bounded queues

- Always shut down executors gracefully

- Monitor queue depth, active threads, and rejection counts

- Separate executors by responsibility

Small misconfigurations compound into large failures at scale.

Conclusion

ExecutorService simplifies concurrency—but only when used deliberately.

Understanding thread pool internals, execution tradeoffs, and workload characteristics is essential to building fast, reliable, and scalable Java applications. Small configuration mistakes often remain invisible until systems are under real production load.

Thread pool design directly influences backend latency, throughput, and system stability. To understand how ExecutorService fits into a broader performance and scalability strategy across client, network, server, and data layers, read:

👉 REST API Performance Optimization: Concepts, Tradeoffs, and Best Practices

Hands-On Examples on GitHub

This article explains the concepts and tradeoffs behind ExecutorService & Thread Pools in Java. For practical, runnable examples, check out the GitHub repository below.

👉 View ExecutorService & Thread Pools Examples in Java on GitHub

FAQ — ExecutorService & Thread Pools in Java

How do I choose the right thread pool size?

Base sizing on workload type. CPU-bound tasks should match available cores, while I/O-bound tasks may require more threads.

Why is my ExecutorService slow?

Common causes include blocking tasks, undersized pools, unbounded queues, and shared executors across unrelated workloads.

Should I use CompletableFuture or ExecutorService?

CompletableFuture is built on top of executors. You still need a properly configured ExecutorService underneath.

When should I shut down an ExecutorService?

Always shut it down during application shutdown to prevent thread leaks and resource exhaustion.

References (Click to Expand)

Java Concurrency & ExecutorService

- Brian Goetz et al., Java Concurrency in Practice, Addison-Wesley.

- Oracle Java Documentation — ExecutorService and ThreadPoolExecutor.

- Doug Lea, java.util.concurrent package design notes.

- OpenJDK Source Code — ThreadPoolExecutor.java.

Thread Pool Design & Performance

- Brian Goetz, “Sizing Thread Pools,” Java.net.

- Martin Thompson — Mechanical Sympathy (thread scheduling & contention).

- Netflix Tech Blog — Thread pool isolation patterns.

- Google SRE Book — Managing load and backpressure.

Backend & System Design

- Martin Kleppmann, Designing Data-Intensive Applications.

- Google Cloud Architecture Framework — Backend scalability.

- Netflix Hystrix Documentation — Bulkhead pattern.

nice.